Episode 3: HTTP and HTTP Response Cycle — What You Need to Know as a Frontend Developer

HTTP is the language of the web, but sometimes it feels like trying to negotiate with a stubborn toddler. You ask nicely (GET), but you might end up with a tantrum (500 Server Error) if you don’t get what you want.

Hello frontend techies! 👋 It’s another exciting week for you to go beyond the art of coding; Beyond The Frontend brings you exciting topics and insights to help you develop a solid understanding of frontend skills.

There would be no web without HTTP and no internet without the web. The interrelationship and communications between these paradigms give us what we have today as the internet. Understanding HTTP (Hypertext Transfer Protocol) in the development of web applications and software engineering is fundamental to how data is transferred between the client (user-facing app) and the server.

In this week of Beyond The Frontend, we’ll delve into the evolution of HTTP and discuss its significance in frontend development. If you have not been following this series, do make sure to check out the other episodes for valuable insights and tips to develop your front-end skills.

The web is like a vast ocean of information, and HTTP is the fishing rod we use to fish out the data. Just be careful not to get lost in the lows of HTTP (404 Not Found).

Before HTTP, computers communicated and transferred data between each other through cables, which meant the systems of communication had to be in the same place or building. This brought about the curiosity of communicating and transferring data wirelessly over a network or web resulting in the evolution of HTTP.

For two computers to communicate wirelessly, they must be able to communicate and understand the same language; called a protocol. The most popular protocol for web communication is HTTP. HTTP is a means of exchanging information, and data — including HTML documents, images, style sheets, scripts, and more — over the internet by establishing a protocol between the browser (initiator ) and the receiver (server).

HTTP provides a network protocol that web browsers and servers use to communicate. You can see HTTP in the URL when you visit a website (for example, https://cbt.clique.ng/signin). A web browser uses this to request HTML files and other resources from a web server, which are then displayed in the browser with text, images, hyperlinks, and related assets. The web is a magical place where you can find anything you want as long as you know how to craft the perfect HTTP request spell!

The Protocol of Communication

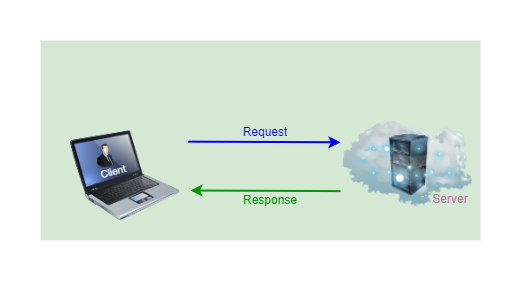

In the definition of communication, it is said to be a process whereby meaningful information is defined and shared between two or more parties. This requires the sender and the recipient, and the process is complete when the receiver understands the sender. This is exactly how HTTP works. If you enter a URL path or address into your browser, the browser first looks up the address of the server associated with the URL and tries to open a connection (communicate) or listen to it on port 80, the default port for HTTP traffic.

Browsers are like the delivery trucks of the internet, transporting HTTP requests to their destinations. Just hope they don’t take a detour through the ‘404 — Wrong neighborhood’.

HTTP is like a road trip; you plan your route (URL), hop in the car (browser), and it takes you to your destination (server). First, you initiate the communication through a URL (Uniform Resource Locator) address. By doing this, a meaningful line of information has been established between your computer and another computer, which may act as the server. The server is now listening to your message (request) through the protocol it has established on port 80. If the server exists and accepts the connection (i.e., understands your message), it will send the browser response information regarding your request, and communication is complete and closed until further request.

Let’s dissect the request URL to the server. You send a request to get clique.ng:

The first part (protocol) tells us that this URL uses encrypted HTTPS — Secured Hypertext Transfer Protocol (i.e., the ‘s’ — Secured) as opposed to non-encrypted HTTP (i.e., which would just be http://). Then comes the part that identifies which server or domain we are requesting the document from cbt.clique.ng. The last part is a path string that identifies the specific document (or resource) we are interested in (sign in page).

If you type this URL into your browser’s address bar, the browser will try to retrieve and display the document at that URL. First, your browser has to find out what address cbt.clique.ng refers to. Then, using the HTTP protocol, it will make a connection to a Transmission Control Protocol (TCP). A TCP connection is where one computer listens to another computer for a request. To listen to different kinds of communication or multiple requests, each listener has a number called a port associated with it. So, assuming cbt.clique.ng is on port 80, the server (listener) at that port address asks for the resource signin.html . If all goes well, the server sends back a document, which your browser then displays on your screen.

The server’s response also includes the status of the response, first as a three-digit status code and then as a human-readable string. Status code 200 (OK Status) starting with a 2 indicates that the request succeeded. Codes starting with 4 means there was something wrong with the request. A 404 is probably the most famous HTTP status code — it means that the resource (i.e., what you are requesting) could not be found. Codes that start with 5 mean an internal error happened on the server and the request is not faulty.

HTTP VS HTTPS — What is the Difference

HyperText Transfer Protocol (HTTP) and HyperText Transfer Protocol Secure (HTTPS) are both protocols used for transferring data over the network. The main difference between the two is the level of security they provide. HTTP does not use an encrypted protocol; on the other hand, HTTPS uses SSL (Secure Sockets Layer) or TLS (Transport Layer Security) to secure the connection. In HTTP, data is transmitted in plain text, making it vulnerable to interception by unauthorized parties, while HTTPS encrypts the data transmitted between the client and the server, converting it into an unreadable format to protect it from unauthorized access.

The server does not verify the website you are trying to access when transmitting data between the client and the server using HTTP, but verification is done to verify that your browser is connected to the right server in HTTPS. This helps prevent CSRF (Cross-Site Request Forgery) attacks and prevent man-in-the-middle attacks by ensuring you are communicating with the intended server. If any unauthorized request is detected, the connection is terminated, maintaining the integrity of the communication.

Request and Response Cycle

Understanding how HTTP request and response cycles work is crucial for frontend developers, as it influences how web applications are designed, developed, interact with backend services, and optimized for performance. The Request-Response Cycle is the fundamental process underlying communication between clients (such as web browsers) and servers in the context of the HTTP (Hypertext Transfer Protocol) protocol. This cycle governs how clients request resources from servers and how servers respond to those requests.

The cycle begins when a client (a web browser) initiates a request to a server. This request is triggered by actions such as entering a URL in the browser’s address bar, submitting a form, clicking a link, or making an AJAX (Asynchronous JavaScript and XML) request. The client establishes an HTTP protocol request which may use any of the HTTP methods (GET, POST, PUT, DELETE, etc.) to specify the action the client wants to perform. The URL identifies the resource (document, file, data) the client wants to access from the server associated with the URL.

For example, when you enter “https://cbt.clique.ng/signin" in your browser’s address bar, a GET request is initiated to fetch the sign page from the server.

Upon receiving the request, the server processes it based on the provided URL method, and any other relevant information contained in the request headers or body. The server performs tasks such as routing the request to the appropriate handler, retrieving data from a database, executing request logic, applying restrictions, and generating dynamic content. After processing the request, the server constructs an HTTP response to send back to the client. The response includes:

Status Line: Contains the HTTP version, status code, and a brief status message (e.g., HTTP/1.1 200 OK).

Headers: Additional metadata sent with the response, such as content type, cache-control directives, and cookies.

Body: The actual content of the response, which could be HTML, JSON, XML, images, or any other type of data requested by the client (browser).

Once the browser receives the response from the server, it processes the data according to the request’s purpose. For example, if the request is for a web page (HTML document), the browser renders the HTML content. With the response processed, the response cycle is complete. Depending on the application’s requirements, the cycle may repeat multiple times during a user’s session, as the user interacts with different parts of the application or performs various actions.

For instance, after login into the platform, clicking on a specific link(route) might initiate another GET request to fetch detailed information about that link or page.

Throughout the cycle, error handling plays a crucial role in ensuring smooth communication between the client and server. Error responses (e.g., 404 Not Found, 500 Internal Server Error) inform the client about issues encountered during request processing.

This episode adds a layer of abstraction between what we have covered about asynchronous operations and requests in the previous episode. It bridges the gap between the request and the method employed in performing those operations.

HTTP formed the foundation of communication on the web, shaping how we design and optimize web applications. Understanding the inner workings of HTTP, including its request-response cycle, methods, status codes, and asynchronous communication, is essential for building high-performance and responsive frontend engaging user experiences.

Below is a link to some other good stuff around the web to help you better understand this concept.

Some Other Good Stuff Around The Web

Thank you for journeying Beyond The Frontend with us! Don’t forget to follow me for future updates and support our work.